Depending on your worldview, you can see the CCCC as many things: guild, advocacy group, social club, publishing house, think-tank, NGO, research sponsor, and so on. But something you don’t really see at the convention is our role in representing our multi-faceted discipline to outside entities whose work impacts us.

Recently, the US Department of Health and Human Services has been soliciting feedback about proposed rules that would govern the protection of human subjects who participate in research projects. After considerable examination of the proposed rules, the CCCC decided to submit an official comment on the rule (see below).

Why worry about human subjects protection? Many of you do work on texts, images, videos, and other objects, and since they’re not people, those things do not fall under the category of human subjects.

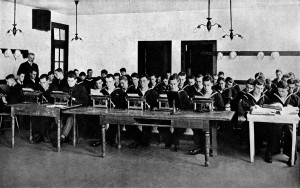

However,  many of us research people: ethnography, case study, classroom study, oral history, interview, literacy narratives, think-aloud protocol, and contextual inquiry, to name a few. And all of those approaches involve studying other humans; thus the proposed rule could have quite an impact on our field’s research.

many of us research people: ethnography, case study, classroom study, oral history, interview, literacy narratives, think-aloud protocol, and contextual inquiry, to name a few. And all of those approaches involve studying other humans; thus the proposed rule could have quite an impact on our field’s research.

This CCCC action originated with the CCCC Research Committee. Member Bradley Dilger coordinated their response. Their hard work—aided by the considerable wisdom of Karen Lunsford and Heidi McKee—deserves our thanks. To learn about tools integral to understanding the 500-page NPRM, please see Dilger’s site, which documents their process.